In Shadow, the chestular character (Shadow) has just recovered from the events of Sonic Heroes, where he was inexplicably found in a capsule after what was supposed to have been a certain demise in Sonic Adventure 2. His memory of all those events and his entire past completely erased, he sets out to find out who and what he is. Just as he does so, aliens drop in from out of nowhere and their leader, Black Doom, claims to know everything about him, saying he'll reveal everything about Shadow's past if he helps him find the chaos emeralds.

The game progresses through stages in more or less the traditional Sonic fashion; every level is a run through an obstacle course to the finish line as well as a war zone, with Black Doom's alien hordes battling humans and Shadow caught in between trying to decide who to support. The player is presented with three goals--"hero," "dark," and "neutral," each of which results in completing the stage. Neutral can be described as simply reaching the end of the stage while "hero" and "dark" concern themselves with more specific challenges, like killing all aliens, killing all humans, collecting specific objects, et cetera. All three are mutually exclusive.

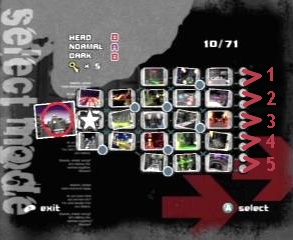

(Above: Level grid from Shadow the Hedgehog)

Depending on which of these goals players choose to complete the next stage they play will be different, with the player moving along a grid corresponding to how good or how evil they decide to play; the central path is totally neutral, the lower path is totally good, and the upper path is completely evil. Whatever path Shadow takes, he's eventually forced to make a choice at the final stage, skewing him towards a "good" or "evil" version of one of the game's many end bosses and one of multiple different possible endings to his story. The game very literally branches in one direction or another at every stage, presenting the most literal and most visible interpretation of a "branching narrative" in any game.

Very clear pitfalls are demonstrated with this decision-making paradigm. The architecture forces the developers to contrive some "good" or "evil" equivalent goal in every level but the ones farthest to either side. Additionally, not every progression makes any kind of narrative sense, with disjointed locations tied together by the weak premise that Shadow just magically teleports between them and plot elements frequently raised and forgotten along any particular route. Several paths, for example, simply drop the premise of Black Doom's invasion completely in favor of a storyline that adopts series mainstay Dr. Robotnik as the main villain, changing premise mid-game. Depending on what the player decides to do Shadow may meander down this alternate plot for a while only to return to the Black Doom storyline inexplicably at the very last stage with no reasonable explanation. A few paths have some logical connection, but many demonstrate glaringly obvious inconsistencies, like Shadow suddenly finding himself in space after spending the entire rest of the game on Earth. These disjoints in staging and plot are often accompanied by considerable disjoints in characterization as well, with Shadow following a plotline where he believes himself to be a robot clone of himself and then suddenly changing his mind about it as if he'd never undergone any of that character development at all.

These disjoints and inconsistencies are characteristic of the worst-case scenario of the branching narrative scheme. Yes, it does branch and react to the player's decisions, it does present a significantly different level flow based on those choices--IE, there's significant consequences--but it also produces a largely incoherent story fraught with irrelevant and contrived episodes and inconsistent characterization. Furthermore the actual player choice element is highly repetitive and extremely shallow, effectively boiling the decision-making down to picking a different door at the end of each level.

Because of the inconsistency of the game's episodes the sense of causality is also very shallow, with players being unable to reasonably predict what the consequences for choosing the "good" or "evil" path at any given time actually are or what kind of level they'll be led into next. It doesn't give the sense that Shadow is making decisions that affect the course of the game's narrative (IE who's winning and who's losing the aliens vs. humans conflict) so much as the sense that he's literally taking different paths through the same narrative, moving through different sets of events running parallel to one another in different locations, with his presence at those events having no impact on what happens in the story whatsoever until the very end.

This may come as a shock coming out of a post-Dreamcast Sonic game, but it's all a very unsatisfying and downright clumsy choice scheme showcasing very probably every pitfall there is to developing a decision-making paradigm for a game. The polarized values lead to highly inconsistent characterizations and narratives, the over-development of the grid system enforces more possibilities than the developers could account for, and every single stage is forced to contrive goals relating to these alternate paths that very frankly don't always mix so well with the forward momentum of a Sonic game. In fact, in order to compensate for the fact that very often it's impossible to go backwards and search for items the player may have missed, the developers had to incorporate a teleporter at the end of each stage that would loop players back to the beginning. If this isn't an effective illustration of how morality is definitely not a one-size-fits-all-games decision-making paradigm, it's at least an effective illustration of exactly how not to build one. In the future we'll definitely see echoes of some of the problems highlighted here, most particularly character inconsistencies, overly consistent, un-engaging choices, and lack of foreseeable causality, but not to the degree where we see all of these in the same game.

No comments:

Post a Comment